Business Times Singapore Investment

Roundtable

Currency war threat not over yet

Besides liquidity, inflation and protectionism are also stalking global economy; but Asia will emerge on top from rebalancing

William R. Thomson

Dec 1, 2010

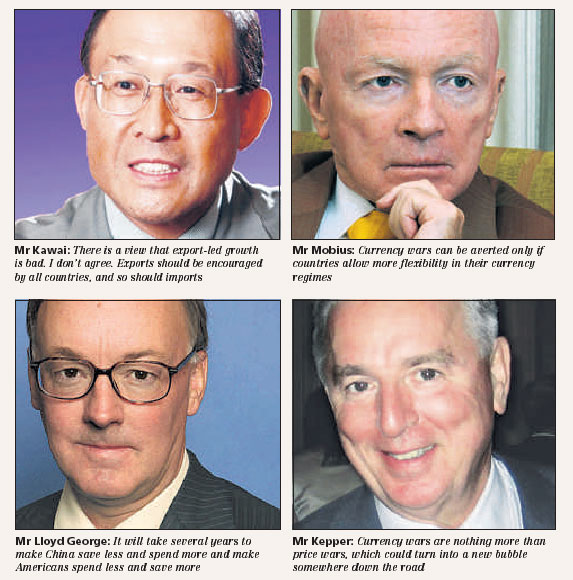

PANELLISTS

Masahiro Kawai: Dean of the Asian Development Bank Institute (ADBI), Tokyo and former World Bank

chief economist for East Asia

Mark Mobius: Executive chairman, Templeton Asset Management

Robert Lloyd George: Chairman, Lloyd George Investment Management, Hong Kong

Ernest Kepper: President, Asia Strategic Investment Associates Japan

William Thomson: Chairman of Private Capital, Hong Kong, director of Finavestment, London

MODERATOR

Anthony Rowley: Tokyo correspondent for The Business Times

FOR the moment, Ireland’s sovereign debt crisis

(and other crises looming in the eurozone)

has pushed the threat of currency wars off the

front page. But it has not gone away. What we

have seen so far are only the first skirmishes

in a “phoney war”. As the flushing liquidity

that is prompting these clashes grows to a tidal

wave, inflation and protectionism are other

spectres that are stalking the global economy.

These are the sobering predictions of economic and investment

experts invited by The Business Times to give

their views on 2011. But they are all of a view that Asia

will emerge uppermost from global economic rebalancing.

Meanwhile, investors need to hedge against uncertainty

by going for gold and other tangible assets.

Anthony Rowley: Welcome to this Business Times Investment

Round Table, and a special welcome to our new

guest, Masahiro Kawai, dean of the ADBI. Kawai-san, let

me begin by asking you whether you think currency wars

can be averted and, if not, which currencies are likely to

be most bruised – or unscathed – by the battle.

Masahiro Kawai: They can be avoided provided policy responses

of non-US economies are conventional, such as

currency market interventions and capital inflow controls. The most reasonable response for emerging economies

would be to limit short-term capital inflows, to allow

currency appreciation and to strengthen supervision so

that inflows will not create a build-up of systemic financial

risks like real estate bubbles. In Asia, this would be easier

if economies, including China, Asean countries and

others, allow currency appreciation collectively. But if

such responses are not adopted, countries with flexible

exchange rates and free capital mobility could be hit the

hardest, as their currencies would be forced to appreciate.

Quantitative easing, or so-called “QE2”, by the US Federal

Reserve is generating a lot of concern among emerging

economies that it will induce competitive US dollar depreciation

and hence can have beggar-thy-neighbour impacts

on these economies. Differential speeds of recovery

among advanced and emerging economies such as those

in Asia have been creating capital inflows to the emerging

markets and QE2 is adding pressure.

Mark Mobius: I agree. Currency wars can be averted only

if countries allow more flexibility in their currency regimes.

Unfortunately, that does not seem to be possible

given the stance of a number of them. No currency will escape

being impacted by continuation of the present situation.

There will be both winners and losers and it hard to

predict which in the short term.

William Thomson: As is so often the case, the decision on

whether currency wars can be avoided is mainly in the

hands of Americans. It seems most unlikely (they can be

avoided) since the US has a policy goal of doubling exports

over a five-year period. A cheaper dollar is an essential element

in this process, especially against Asian currencies. A second US objective is to avoid deflation at all costs and

make sure there is some inflation in the system. This

means further quantitative easing on a scale yet to be determined.

The Fed has announced an additional US$600

billion through June 2011. When added to the US$300 billion

refinancing of maturing mortgage bonds, the total QE

so far is US$900 billion – sufficient to finance all the budget

deficit in that time frame. What comes after is uncertain

but if Goldman Sachs is to be believed, the final amount of

QE required could total over US$4 trillion in coming

years.

The worst-hit currencies are likely to be what I call the

three “ugly sisters”: the dollar, the pound and the euro. All

are heavily indebted, with ageing populations and troubled

banking systems. The euro remains a lopsided construct

in a non-optimal currency area. Problems remain

with the “PIGS” countries where the real issues have yet

to be dealt with. The “winners” should be those of commodity-

producing countries and export giants such as

Canada, Australia, China, South-east Asia, Norway and

possibly some Latin American countries such as Chile.

Ernest Kepper: The currency war declared by the US has

massive implications and cannot be averted. The US can

win, since it has all the ammunition it needs – there is no

limit to the dollars the Federal Reserve can create. Understand

that this option is not available to other central

banks as the dollar is the recognised reserve currency, in

lieu of gold. Currency wars are nothing more than price

wars, which could turn into a new bubble somewhere

down the road. Once one or two big countries start a price

war everyone has to join in, either to protect their currency

reserves balance or like Brazil and others to stop their

currencies from going up so fast.

The US has depreciated the dollar roughly 13 per cent

against the other major currencies since June. The intent

is clear: The Fed is enacting “easy money” policies to debase

the dollar and reduce the value of foreign debts,

while representing the falling dollar as the outcome of a

policy to boost inflation and spur the economy and increase

employment. Devaluation will be achieved by flooding

currency markets with dollars, providing the kind of

destabilising opportunities that fit perfectly computerised

currency trading, short selling and pure profit-seeking financial

manipulation.

Such speculation is a zero-sum game. Someone must

lose – and the emerging market countries will. So, countries

like Brazil, Thailand and South Korea are taking defensive

measures. In the 1997 Asian crisis, Malaysia

blocked foreign purchases of its currency to prevent

short-sellers from covering their bets by buying the ringgit

at a lower price later, after having emptied out its central

bank reserves. The blocks worked, and other countries

are now reviewing how to impose such controls.

The currencies to own in this situation are Singapore

dollar, Norwegian kroner, Australian and Canadian dollars,

based on their natural resource economies. The renminbi

is his most undervalued currency today. All you

have to do is to forecast the next salvo in the currency

wars, and to position yourself to take advantage of it. We

are going to see extreme volatility going forward.

Robert Lloyd George: I believe that as we approach the

end of 2010, we are moving inexorably towards a world

currency regime, probably with some component of gold,

or gold standard, as was suggested by Robert Zoellick,

president of the World Bank. The US dollar is clearly losing

its credibility as the anchor of the world monetary system

at an even faster rate as Ben Bernanke embarks on

QE2. This global currency may take a form similar to the

euro, with the weaker currencies, such as the US dollar being

co-opted into a harder currency regime, as the deutschmark

dominated the euro when it was established. The yen, euro and renminbi will form the core of this new

world currency. The currencies that are likely to be less

affected by “currency wars” would be of course the Swiss

franc, Norwegian kroner and the commodity currencies

such as the Australian dollar and Canadian dollars, Brazilian

real and perhaps the Russian rouble.

Anthony: So, is there another tidal wave of liquidity on the

way given Ben Bernanke’s commitment to 2 per cent annual

inflation in the US, and how much of this liquidity is

likely to wash up on the shores of Asia? How real is the

threat of future inflation from all this liquidity and what

does it imply for equity, bond and and real estate markets

in Asia and elsewhere?

Mark: There is a continuing wave of liquidity but there is

evidence that the rate of increase is declining. Looking at

the success of IPOs (initial public offerings) in Asia with almost

half of emerging market IPOs and secondary issues

taking place here it is clear that a lot of the liquidity – perhaps

as much as a half – is finding its way to Asia.

Masahiro: Liquidity creation by the US at this point, when

many emerging economies are growing in a robust way,

can be the source of future inflation and asset price bubbles

in emerging economies. Commodity price increases

as in the case of gold, metals, minerals, energy and food –

would create inflationary pressure globally and particularly

in emerging economies.

William: A tidal wave of liquidity has been clearly flagged

by the Fed’s actions. Only the ultimate size is in question.

If, as seems likely, there is policy paralysis in the US after

the mid-term elections, monetary policy will be the only

game in town over the next two years. Do not believe the

talk about a 2 per cent inflation goal. The true goal is

much higher since they hope to diminish the real value of

debt and support asset prices, especially housing. But the

policy of inflation requires deception to be effective. Inflation

is on the way as commodity prices and devaluation

work their way through the system. In fact it is here already

but official statistics do not properly capture this

fact.

Asian nations have a choice: either let their currencies

appreciate, or suffer a property and equity bubble, or put

in place currency and lending controls. I expect we will

get a combination of all three over the next two years.

More generally, as long as interest rates are negative in

real terms we will get equity bubbles elsewhere too. Property

is more problematic since banks are being restrictive

with their mortgage lending and unemployment remains

high.

Ernest: By promoting a weaker dollar, the US is creating

dangerous inflationary pressures that will have negative

repercussions globally. As a consequence of QE2 – central

bankers will be forced to intervene in currency markets,

institute ad hoc controls and resort to protectionist policies

to protect their exporters. This can only mean a more

drawn-out and difficult global recovery.

Arbitrageurs and speculators are swamping Asian and

other emerging market currency markets with low-priced

dollar credit to make predatory trading profits at the expense

of Asian central banks which are trying to stabilise

their exchange rates and keep asset prices from rising by

selling their currency for dollar-denominated securities.

Robert: If the Fed prints another US$600billion plus of liquidity,

I would expect that 75 per cent of this will go offshore,

and the large part to emerging markets, notably in

Asia. There is a real danger of inflation reaching 10 per

cent in countries as diverse at India, China, Indonesia,

Philippines, Brazil, Argentina and other fast-growing resource

producers. Our investment strategy is to run an inflation-

hedging approach in buying oil and gas producers,

mining houses, gold, silver, agriculture and real estate, especially

in the Asian hemisphere.

Anthony: There is a great debate about global economic restructuring

in which emerging-market economies supposedly

will put more emphasis on domestic demand and less

on exports and vice versa in advanced economies. How do

you see this working out, and in what kind of time frame?

Masahiro: There is a view that export-led growth is bad. I

don’t agree. Exports should be encouraged by all countries,

and so should imports. All countries cannot produce

net export surpluses, but they can enjoy export-led

growth as long as imports rise everywhere. If each country

shifts productive resources (capital, labour, knowledge,

etc) to sectors where the country has comparative

advantage, then the global economy will become more efficient

in resource use. Also such export expansion creates

more investment and jobs. Free trade should be protected.

Mark: Restructuring is happening right now and this is evident

not only in China but in other emerging markets like

Brazil. Unfortunately, the evidence will be difficult to detect

since stronger emerging market currencies mean that

these economies can import more with fewer dollars.

William: China has clearly signalled in its next five-year

plan 2012-17 that it intends to increase the level of consumption

in the economy from an incredibly low 35 per

cent to around 45 per cent. A higher exchange rate is an

important element in that transition but it must be done at

a rate that does not ruin export industries. Social stability

is the primary goal of Chinese authorities. It will require

reforms in housing, education and the development of social

safety nets. None of these can be accomplished overnight

but I would expect clear progress to be made.

The US and the UK both recognise that their economies

need rebalancing with more emphasis on manufacturing

and less on financial services. That is hard to accomplish

since they are simply not competitive at today’s

exchange rates in most industries. I fear the US will become

increasingly protectionist, especially after 2012 if

the economy remains mired in stagnation. If things are

not going their way, populist anger is likely to make them

rip up the rule book as they did in 1933 and 1971. The

end of empire is never pretty.

Robert: I believe it will take several years to achieve the

restructuring of global imbalances, to make China save

less and spend more and make Americans spend less and

save more. But recession and unemployment in the USA

have had a fairly rapid effect and with the falling dollar imports

will slow down and exports hopefully will increase. In a completely free-floating currency regime, the self-correcting

mechanism should have worked to correct the imbalances.

But as we saw with the yen after the Plaza Accord

in 1985, it does take up to five years.

Ernest: The ongoing shift of global output from developed

economies to emerging economies, particular Asia, will

bring a lot of volatility. Growth may be evident in the

emerging markets but the volume is in the developed countries.

It is unlikely that growth in emerging markets can

make up for the lack of growth in the developed countries. The biggest challenge is that emerging markets achieve

growth from productivity gains rather than from manipulation

of their exchange rates.

Anthony: As wealth becomes more balanced globally under

this process, how will it affect the relative importance

of financial markets around the world. Where will the

pools of capital be located in the future, and where and

how are these likely to be deployed by portfolio investors?

Mark: More capital will be diversified globally instead of

being concentrated in home markets. More will be in equities

although fixed income will still be larger than equities.

Masahiro: Emerging Asia will be wealthier and a larger

pool of savings will be created in Asia. The challenge is to

make financial intermediation more efficient at the national

and regional levels. Japan’s and China’s savings should

be mobilised to finance productive investment in Asia.

William: The Asian financial markets can only grow in relative

and absolute importance since that is where capital is

increasingly generated and the tax and regulatory regimes

are more attractive. London, New York and Switzerland

will not disappear but Singapore, Hong Kong, Shanghai

and possibly Mumbai will grow in importance on a regional

and international level. Middle East regional markets

are likely to become more important in their locality

as their sovereign wealth funds become investors of last

resort.

Robert: I expect that China will be 25 per cent of the world

capital market within the near future. India follows close

behind. The “Frontier Markets” in Africa, for example,

will go from being less than 2 per cent to perhaps 10-15

per cent of world markets. Some 90 per cent of IPOs in the

world are now taking place in emerging markets rather

than in Europe or the US. Before 1800 China and India

were the wealthiest nations in the world and by 2020 it

will be true again.

Ernest: The global financial system has taken on a life of

its own separate from meaningful trade and investment

as dollar outflows do not create assets or provide tangible

investment in plant and equipment, buildings, research

and development. It is more the creation of debt, and its

multiplication by mirroring, credit insurance, default

swaps and an array of computerised forward trades.

Financial conquest is seeking today what military conquest

did in times past. Countries on the receiving end of

this US financial conquest are seeking ways to protect

themselves. Ultimately, the only way to do this is to erect a

wall of capital controls to block foreign speculators from

destabilising currency and financial markets.

Anthony: Commodity-producing and exporting countries

have been on a roll with their terms of trade improving

dramatically. Can this last, and what is the outlook for industrial

and agricultural commodities?

Mark: Yes it can last, given the growing global demand

from the most populous emerging markets. There, of

course, will be great volatility which sometimes will look

like a bear market but it will be merely a correction in an

on-going long-term bull market.

Masahiro: Emerging Asia’s growth will continue to raise

commodity and energy prices. The US easy monetary policy

will help these price rises further.

William: Commodity cycles typically run from 15 to 25

years and we are only 10 years into the present one. If we

are talking about energy, oil demand continues to increase

and new discoveries are inadequate. The emerging

markets have a huge demand for commodities used in infrastructure

and their food demands are growing. Prices

are likely to be quite volatile reflecting cyclical and seasonal

patterns but underlying growth is likely to remains

strong as long as the global economy remains open and

vital. But the West, especially the US, could lose faith in

globalisation. I believe this is a valid fear. I see some unfortunate

straws in the wind.

Robert: The commodity bull cycle will last until 2014, with

agricultural commodities being particularly strong in the

next three to four years, as they catch up in real terms

with oil, gold and mineral prices.

Ernest: There are three broad and major areas of opportunity

that will be generated from the Fed’s move to depreciate

the dollar – currencies, precious metals and stocks

and bonds in emerging markets. Precious metals and

grains will continue their price growth until 2012 or so.

Anthony: Talking of precious metals, will gold go to

US$2,000 an ounce or even beyond in the foreseeable future

and what are the implications of central banks’ decisions

to stop selling gold? What about other precious metals?

Mark: Gold at US$2,000 an ounce is certainly possible and

the same bullish scenarios can be given for such metals

palladium and platinum as well as other metals.

William: US$2,000 an ounce is certainly possible in the

next two to four years. Gold has appreciated about 20 percent

per annum since the lows in the year 2000. Much will

depend on the rate that the US devalues the dollar by printing

more money. If some of the figures I mentioned earlier

for QE happen then US$2,000 would seem to be a lead

pipe cinch. Indeed, we could have a 3 or 4 in front of the

price before the end of the cycle.

But, I do not believe trying to forecast the price is particularly

useful. Gold is part of an insurance policy in a portfolio

rather than a profit centre. I do believe that whilst

bullion will still go up that quality gold mine shares will appreciate

more. I also believe that silver will appreciate

more than gold from here. Platinum will probably trade

like gold but maintain a premium to it since it is rarer.

I found Robert Zoellick’s recent comments about defects

in today’s international infrastructure and the need

to consider some role for gold as a reference for the appropriateness

of current policy interesting. This is the first

time an establishment figure has indicated dissatisfaction

with the post-1971 settlement. I suspect it is the opening

salvo of a new and overdue debate.

More Shine? Gold is seen

topping

US$2,000 an

ounce within the

next six to 12

months, and get

to US$5,000 per

ounce by 2014.

Investors are

told to hedge

against currency

uncertainty by

going for gold

and other

tangible assets.

Robert: I expect gold to top US$2,000 an ounce within the

next six to 12 months, and get to US$5,000 per ounce by

2014. Central banks will be buying rather than selling and

it is completely misleading to suggest that we are in a gold

bubble because it has barely started and the real value is

at least 4 times higher than its current price. The real value,

adjusted for monetary inflation is at least US$5,000. Silver will probably outpace gold, in other words, it will

probably exceed its US$50 an ounce high of 1980. Platinum,

palladium and other precious metals will match or

outpace gold.

Ernest: Gold should reach US$1,500 by year-end, surpass

US$2,000 in 12 months or so, and will reach US$2,500 in

around 18 months. The reasons why gold will go much

higher are that central banks will continue to buy large

quantities as the debt crisis goes global and Europe’s debt

problems are getting deeper. Motivated by either fear or

greed, investors are jumping into gold as they shift away

from the US dollar.

Unless a new currency structure provides that each currency

is backed up by something tangible – the same

game is just being perpetuated. Honest money must be redeemable

by something tangible or real – not just a warehouse

receipt of some sort. That’s why investments in

gold (oil is another tangible investment) are so important

at this time for your portfolio.

Anthony: Thank you all for a stimulating discussion and allow

me to wish you a prosperous New Year in 2011.

###

Nov 29, 2010

William R. Thomson

email: wrthomson@private-capital.com.hk

William Thomson is Chairman of Private Capital Ltd. in Hong Kong and an adviser to Axiom Funds and Finavestment Ltd. in London.

321gold Ltd

|